The Imago Dei

According to Gen. 1:26, 5: 1 and 9:6, God created man in the divine image. Based on these biblical texts, the doctrine of the imago dei was worked out. Patristic writers generally stressed the idea that human rationality and freedom are marks of the divine image.

Men are like God because they possess free will and reason. This was in agreement with Greek philosophy. Aristotle defined man as a rational animal, making him superior to all other creatures.

The Stoics believed that human reason resembles the divine Reason (Logos) which permeates the universe. Hence, it was natural for the Church Fathers to teach that we participate in the nature and being of the divine through our reason. Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons (c. 175), distinguished between the image and the likeness of God. (In Latin, imago and similitude).

For Irenaeus, the image of God consists of rationality and freedom, which characterize every man in his natural state. The likeness or similitude of God was a special gift, through which we had supernatural communion with God before the Fall.

Man then possessed the image and the likeness of God. Because of the sin of Adam and Eve, man lost the similitude to God, but retained the divine image. Even a fallen man possesses reason and free will. What he lacks and longs for is the lost gift of supernatural communion with his Creator.

1 Augustine agreed with Irenaeus that there is a basic difference between the image and the likeness. But he differed at an important point. According to Irenaeus, Adam and Eve were not fully mature when the Fall occurred. They existed in a primitive, unreflective state of innocent immaturity and had just begun the process of becoming full human beings.

However, for Augustine, Adam and Eve were already in a state of perfection at the time of the Fall. Because they possessed both the image and likeness of God, Adam and Eve were perfect in every way-physically, psychologically, morally, and spiritually. Thus, their fall was a terrible calamity.

Aquinas borrowed from both Irenaeus and Augustine to formulate the classic Catholic view. According to Aquinas, before the Fall man was both natural and supernatural. Naturally, he was a rational being, and supernaturally he possessed the gift of grace.

Man can be compared to a house with two storeys, the floor level being the imago dei and the upper storey being the “likeness” of God. In the Fall, the top level was destroyed, but the bottom level was only slightly damaged.

This means that while man lost the gift of saving grace, his reason was unimpaired. The Reformers rebelled against Aquinas' imago Dei doctrine. Luther denied the traditional distinction between the divine image and likeness. He pointed out that the Hebrew author intended the two words as synonyms.

The Genesis text was only a typical example of the poetic parallelism used by the Old Testament Psalmists. For Luther, man is a unity. To possess God's image and likeness means that Adam and Eve were united to God's Word. When they fell, they completely lost the divine image.

Man's reason, like everything else about him, or creative ability, as past theologians assumed. The imago dei does not reside in us, but rather it is the image we present to God: How do we look to God?

How we appear to God depends upon how we relate to others. He is not interested in what we possess, but in how we are connected to our neighbors and Him. Our true image, the image God has of us, depends upon our encounter with Him and other people, as well as the depth of our fellowship with both of them.

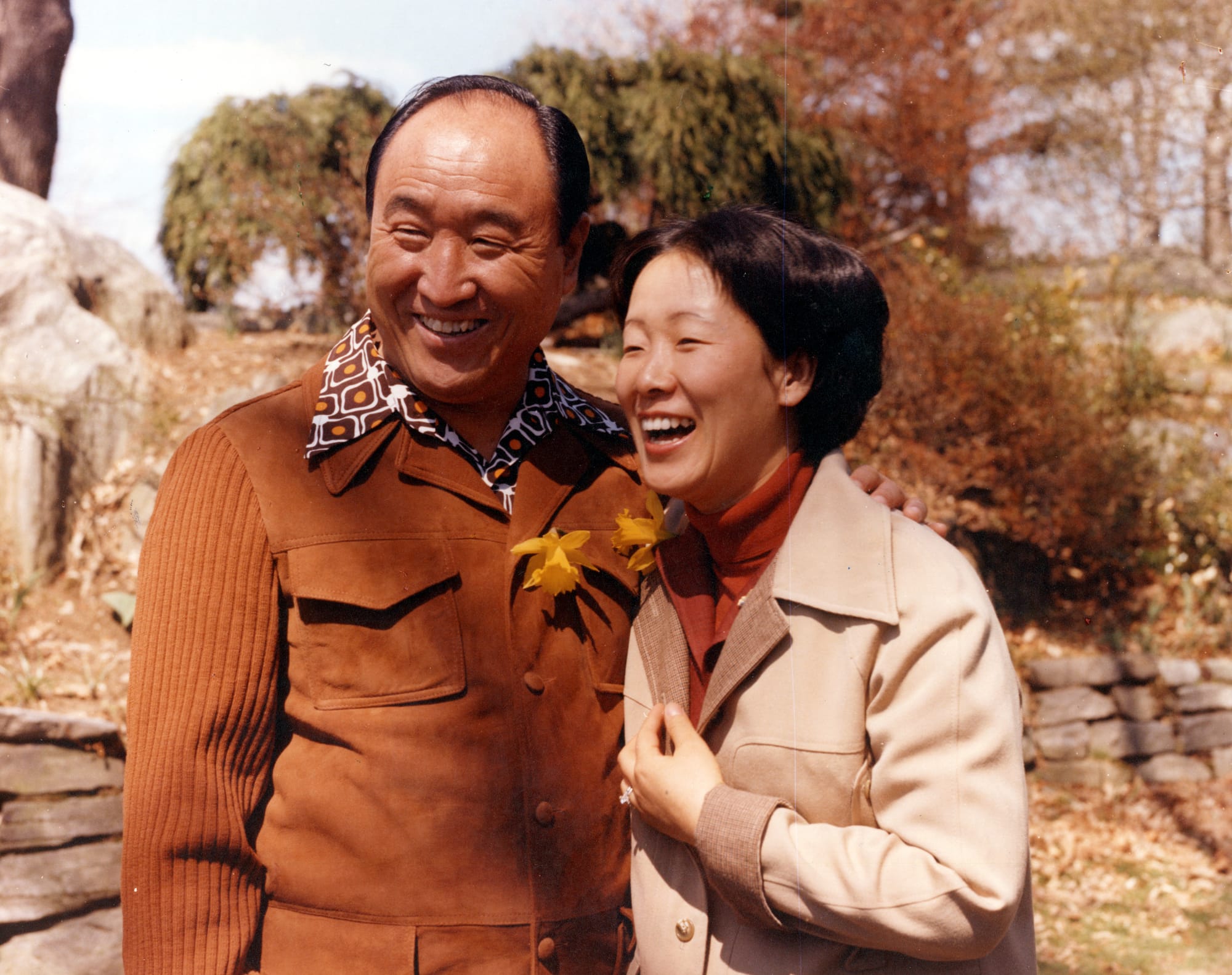

Another interpretation throws additional light on the nature of the imago dei. According to Genesis, “God created man in his image; in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” ( 1 2 7).

This text implies that: 1) like God, every individual also contains both elements. Each man possesses some feminine qualities, and each woman has some masculine characteristics, as Jungian psychology also maintains. 2) The achievement of intimacy, harmony, and creativity of man and woman in the state of marriage reflects God's providential intent in creation. 3) The uniqueness of men and women is found in their distinctive combination of reason and affections, and not in their reason and free will, as other views claim.

Like God, they are unique because they possess a heart. Their loving nature, as well as their intelligence, makes them superior to all lower forms of life and reflects God's image. The concept of the imago dei has far-reaching implications.

Because we are all made in the image of God, we are given inalienable rights and solemn duties. In the ancient world, only the ruler was thought to be made in the divine likeness. The Pharoah alone was the son of god.

Later, the imago dei doctrine gradually led to the democratization of personal rights. In the Puritan movement in England and the American Revolution, this doctrine was used to prove the rights of the individual and to resist oppressive governments and absolute monarchy. Furthermore, this belief has economic and ecological depraved.

The whole man became self-centered rather than God-centered. Among modern theologians, Brunner revived Irenaeus' theory. Man feels he should and must respond to God, but in actuality, he is unable to do so because he has lost the ability.

Barth opposed Brunner's interpretation, seeing it as a revival of the natural theology that he denied. Barth agreed with Luther that there was no textual or other doctrinal reason for separating God's image from His likeness. However, Barth went far beyond Luther by stressing the rest of the Genesis passage.

What is the imago dei?

Scripture explains that God created male and female. We are created in relationship to others. The divine image does not mean something possessed by each person. The imago dei signifies a man's love relationship to another person. We are created male and female to fulfill our need to love.

At least in a physical sense, we still have this ability even in our fallen state. 2 For Barth, the Old Testament concept of the imago dei was continued and completed in the New Testament.

Jesus Christ manifested the true image of God in his love for his Church. Jesus and his people are related by their love. Thus, the God whose essence is agape fulfills His purpose for creation through the unity of love between Christ and His Church. (Col. 1:24; 2:9-13).

What does the word 'image' signify?

There are two possible meanings. An image can be stamped on a coin, as the Romans stamped a picture of the reigning Caesar on their money.

In this case, if we possess the image of God, a divine faculty has been impressed upon our human nature. Or, an image could be our reflection in a mirror. If we turn our backs on God, we cannot reflect our proper image.

First, many theologians define the divine image, but the second may give a better analogy. The imago dei is not some human characteristic. It is not our reason, our soul, our moral capacity,y cal implications.

The imago dei concept gives man a right to ·. Rule over creation. God commands us to be His responsible partners in protecting and nurturing the world around us. B.

The Nature of Man

There have been numerous definitions of man in the past and there are still serious disagreements over the meaning of being human. Aristotle described man as a rational animal.

Today, a very popular book calls man The Naked Ape, meaning that we are not superior to other animals, and only differ from apes because they have fur, and we do not.3 Feuerbach once wrote that man is what he eats.

Jean-Paul Sartre says that man is a “useless passion,” because there is no God and therefore no purpose in the universe. Pascal defined man as a curious mixture of so much misery and so much glory.

Thus, man has been variously described as a rational animal, an economic animal, an evolving animal, a depraved sinner, and a son of God. Our modern view of man originated during the Renaissance.

In conscious opposition to medieval asceticism and otherworldliness, human nature was given a positive interpretation, as is illustrated in Shakespeare's Hamlet: What a piece of work is man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties; in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god: the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals! (Act II, 2:300-303).

Such was the typical Renaissance concept of man. However, Shakespeare was not blind to human frailties and follies. So Hamlet, the melancholy Dane, adds to his praise of humanity a significant line: “And yet to me, what is this quintessence of dust?”

Ever since the Renaissance there has been a rivalry be, tween the positive and negative views of human nature. Some have extolled man's nobility: his reason, scientific discoveries, technological inventions, physical beauty and moral insight.

Others have pointed out the glaring faults in human nature.

How does contemporary theology view man?

Since World War I, European theology has defined man in terms of his responsibility to God.

Firstly, we possess purposive freedom. It is not freedom from something, but for something. We are free before God so that we can have fellowship with Him.

This responsibility distinguishes man from every other creature. The essence of man is to be for God. We do not live for nothing. Nor do we exist for ourselves, as individualists believe. We were created for God and our fellow men.

4 In Jesus Christ, we see what man is supposed to be. He was “the Man for others,” in Dietrich Bonhoeffer's words. We find our reason for existence in our duty to our common Creator. Man was made to be God's covenant partner. We were created to respond freely to God's gift of grace.

Reciprocity with God was the ground of our being and is our destiny. So man's nature should be defined in terms of his responsibilities. Secondly, man lives in togetherness with others. No one is supposed to exist in isolation. In the ultimate sense, God is not interested in us as individuals. He is primarily interested in each of us as part of a larger community.

Our humanness depends upon the encounter with others. A person is largely shaped by his culture: the customs, language, moral standards and religious traditions of his society.

If someone was brought up with only animal companions, he could not talk or think or feel like a human being. We have our being in encounter. What does this mean? First, being human is to be able to look at others directly. We can only see ourselves as we see others.

Our humanity originates in our openness to one another. Without this openness, our meeting is inhuman, an I-it relationship. An I-thou relationship implies both speaking and listening. Each of us needs to communicate with others. Each must try to interpret himself to others.

So we become human to the extent that we achieve real conversation, genuine intercourse, and true mutuality. Being human also means lending a helping hand. We must live for our neighbors.

One's humanness is demonstrated in deeds of loving kindness, as Jesus taught in his parable of the Good Samaritan. We become truly human by hearing somebody's call for help and responding to it with deeds of service.

Thirdly, to be human is to be limited. Man, like the animals and plants, is merely a creature. We live in time and are bound to it. Only God is eternal. Each person is conditioned by their past, present, and future.

We have a beginning and will come to an end. Unlike God, man is limited by temporality, finitude, and creatureliness. However, there is no sin in being finite. What is sinful is for the creature to think himself equal to the Creator and set himself up as a rival to God.

In the fourth place, man lives for the future. It is natural for man to look ahead. It is a part of his humanness to be filled with hope. Animals live in and for the present; their awareness is limited to immediate sensations. They have no memories and no interest in the future.

They live from one day to the next. Man is distinctive because he can recall the past and anticipate the future. Because we are human, we feel the future always coming toward us.

As the theologians of hope insist, God beckons us from the future. Since it is part of the essence of man to be filled with hope, hopelessness marks the end of man. When hope disappears, men feel bound by fate. If we feel we have no freedom to control our destiny, we feel oppressed and depressed.

Hopelessness, therefore, makes us less than human. Man's history can be called a polarity between destiny and freedom. We are limited and conditioned by our past and our present surroundings.

No person is free. At the same time, we are not fatalistically determined. A wide range of possibilities is always open to us. We can select a certain possibility and decide. Hence, it is natural for men to look hopefully toward life ahead. Tomorrow can be better than today, we believe.

Reinhold Niebuhr used to say that man has the ability of self-transcendence. We do not have to accept ourselves as we are; we can look at ourselves, evaluate ourselves, and change ourselves. Man is open to the future. T-J So far, we have dealt with the doctrine of man as taught by the theologians of crisis like Bonhoeffer, Barth, and Brunner.

This is also the modern psychosomatic view of man taught by Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, and other existentialists. Since World War II, German theology has somewhat changed.

Wolfhart Pannenberg now stresses the Biblical teaching that God chose man to have dominion over all creation. We are expected to be God's representatives on earth. He has given us the right to rule and control the earth. This is man's chief privilege. But such an idea should be used with caution.

Man is not just the lord of creation. Man is expected to be the earth's caretaker as much as its ruler. 6 So far, we have looked at God's original creation and His primal purpose for man. We have deliberately ignored the effect of sin, which will be treated later.

References

I John Hick, Evil and the God of Love (London: Fontana, 1974), pp.

207-224.

2 K. Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol III, pt. 2 (Edinburgh: T & T Clark,

1974), pp. 291 ff.

3 Morris Desmond, The Naked Ape (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967).

4 J. W. Woelfel, Bonhoeffer.Js Theology (Nashville: Abingdon, 1970), pp.

60-68.

5 R. Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man, vol. 1, (New York: Scrib-

ners, 1949).

6 W. Pannenberg, Human Nature, Election, and History (Philadelphia:

Westminster, 1977), pp. 13-41.