Proofs of the Existence of God

How can we know that there is a God?

Most people who believe in God do so because that is what they have been taught. Their parents told them, or they learned about God in Sunday School.

They know that God exists because it says so in their Catholic catechism, or because they were convinced by a TV religious program.

However, belief in God is no longer as common as it once was. Public opinion polls tell us that more little children believe in God than do teenagers, and more college graduates are agnostic or atheist than high school graduates. Are there any convincing proofs for the existence of God?

Can one believe in God based on reason? 1 First is the well-known ontological argument for the existence of God, worked out by Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century.

The argument, developed in two stages in his Proslogium, defines God very precisely as that being than which nothing greater can be conceived (not as the greatest possible being or the most perfect being).

The first version of the ontological proof argues that a being that exists in reality is greater than a being which exists in the mind alone, and thus that being, than which nothing greater can be conceived (i.e., God) must exist in reality, and not just in the understanding.

This weak form of the argument has easily been refuted from Anselm's time on.

One can, for instance, say that $100 in real money is better than $100 in imaginary money; so the $100 must exist. And this is not so. But Anselm's second version of the ontological argument is far more powerful; it involves the superiority of a being that exists necessarily over a being that only exists contingently.

Since a being than which nothing greater can be conceived must exist necessarily, then God must exist necessarily.

Necessary existence must be thought of as an attribute of God, since it is superior to contingent existence if one thinks of God as that being than which nothing greater can be conceived-and, as Charles Hartshorne has pointed out, this argument only works for those who are willing to think about God (whether they believe in God or not); those who reject the very notion of God as nonsensical cannot participate in this dispute.

If God is thought of as having the property of necessary existence, then there are two possibilities:

1) God exists; or

2) God does not exist.

1) is so, then God exists, which is what the argument is trying to prove.

But if 2) can even be conceived of) is possible at all, then we have departed from the stated definition of God as a being whose non-existence is inconceivable; for one who might not exist, even if He does exist, does so contingently.

Thus, 2) is ruled out, so God exists necessarily. Modern logicians such as Hartshorne and J. N. Findlay have developed the stronger form of Anselm's ontological argument into a subtle and highly technical modal argument that is scarcely accessible to those lacking training in symbolic logic.

I will not deal with it here; it suffices to say that the ontological argument, far from being shallow and easily refuted, is considered by many contemporary philosophers and theologians to be strong and by some at least, entirely valid proof of the existence of God.

Traditionally, the most common proofs for God's existence are the cosmological and teleological proofs. From the cosmological angle, we say that the creation and maintenance of the universe require a powerful and intelligent God.

This was the proof of the existence of the divine used by Plato and Aristotle, and further elaborated upon by Aquinas. Archdeacon Paley stated it most simply, as follows: If a watch requires a watchmaker, then our complex world necessitates a divine creator.

In a 1948 radio debate with Bertrand Russell, the Jesuit theologian F. C. Copleston used this cosmological argument to prove God's existence. According to Copleston, God exists, and His existence can be proved philosophically. We know that none of the material objects in the world is self-caused.

Therefore, they must have an external reason for being. Since we cannot imagine an infinity of dependent beings, there must be a prime mover and first cause, God.

Numerous scientists have accepted this cosmological proof: astronomers like Sir James Jeans, physicists like Sir Arthur Eddington, biologists like Alister Hardy, and paleontologists like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

According to them, our universe is so complicated, so intricate, that it had to be made by a superhuman intelligence, which we call God. Mere chance cannot explain our kind of world. As the philosopher Michael Polanyi put it, no monkey can produce a play like “Hamlet” by pounding on a typewriter at random. Neither can mere chance have caused our world.

The teleological proof for God is built on the notion that creation exhibits purposiveness. There are numerous small-scale designs in nature and an all-inclusive cosmic design. Let me mention only one small piece of evidence, cited by the modern Scottish philosopher A. E. Taylor.

Some species of insects always lay their eggs on the leaves of certain trees, which provide suitable nourishment for their grubs. The egg-depositing insect will die before the eggs hatch; its egg-laying habit is unconscious, purely instinctive, and of no benefit to the insect itself.

Taylor holds that this “prospective adaptation” supports the view that there is a purpose in nature;5 this designed activity is part of the overall purpose of God.

Stanley Jaki, a priest and scientist, maintained in his Gifford Lectures that science itself depends on the Christian belief that there is a rational plan for all nature. 6 Immanuel Kant developed a moral proof for God's existence, based on the requirements of the moral law.

Since those who do good are not always rewarded in this world, nor are evildoers always punished, we must postulate immortality so that justice may be done in the next life. And God is required to guarantee the workings of the moral law as a postulate of practical reason, not of theoretical reason.

God cannot be merely a part of nature, for then He too might be subject to the failures of justice noted above; He must be “a cause of all nature, distinct from nature itself,” containing the “principle of the harmony of nature” with “a causality corresponding to moral character.”

Kant concludes that, as a foundation for all moral duties, “it is morally necessary to assume the existence of God.”

Hastings Rashdall ( 1858-1924 ), a well-known British religious philosopher, agreed with Kant. We cannot show the validity of a moral ideal on naturalistic or materialistic assumptions.

The idea of an unconditional, objectively valid moral law undoubtedly exists, as a psychological fact. All men recognize the authority of conscience. Belief in the righteousness of God forms the very heart of morality and guarantees moral objectivity. We must recognize the existence of a Mind whose thoughts are the standard of truth and goodness.

There is also an experiential proof for the existence of God, which has two forms.

On one hand, there is sociological evidence that belief in the supernatural exists in all cultures, whether primitive or advanced.

On the other hand, the existence of God can also be demonstrated based on personal religious experience. The mystics know there is a God because they have felt His presence.

These proofs for the existence of God were used by William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience and by the French philosopher Henri Bergson in his book, Two Sources of Morality and Religion.

A recent approach to proofs of the existence of God views them as inductive, rather than deductive arguments, and assesses them according to the logic of Confirmation Theory.

Richard Swinburne, in his book on this topic, explains that while inductive arguments are not valid (or invalid), as are deductive arguments, nevertheless, there are clear standards for judging inductive arguments to be correct or incorrect. A correct inductive argument is one whose premises support its conclusion, i.e., make it more likely than not (or more likely than some other hypothesis).

But more than this is required for meaningful discourse, especially when the argument deals with the existence of God. The premises of a good inductive argument must be agreed on by those who dispute its conclusion, at least initially.

In the case of arguments for the existence of God, the premises must be such that all theists and atheists can agree on them. According to a theorem of Confirmation Theory, particular evidence only confirms one of two otherwise equally probable hypotheses if, given that hypothesis, the evidence is more probable than it would be, given the other hypothesis.

Likewise, a hypothesis is only confirmed by evidence if the evidence is more likely to occur if the hypothesis is true than if it is false.

The postulation of an omnipotent, omniscient, all-benevolent God as the creator of the universe is an elementary hypothesis, which by the normal standards judgment of scientific hypotheses gives it a considerable edge over competing hypotheses, such as that: 1) the universe is caused by a being lacking God's infinite properties, or 2) the universe has no cause or explanation.

For example, about the cosmological argument, Swinburne says there is quite a chance that if there is a God, He will make something like our finite and complex universe. It is very unlikely that a universe would exist uncaused, but rather more likely that God would exist uncaused.

The existence of the universe is strange and puzzling but can be made comprehensible if we suppose that it is divinely created. This supposition postulates a simpler explanation than does the supposition of the existence of an uncaused universe, and that is a ground for believing the former hypothesis to be true.

Does God exist? When Hans Kling published an 839-page book on that question in 1979, it became a bestseller in Germany. If there is no reasonable evidence for belief in God, then religious people are in real trouble. Very few these days will accept an idea of faith alone.

We may not come to believe in God, love Him, and trust Him based on logical arguments, but many people will abandon their religious beliefs if reason and all the rational evidence point toward atheism.

From this standpoint, finding proof for the existence of God is as necessary now as it was in the time of Anselm or Aquinas. And, as Kung says, if people lose their faith in God, our world is doomed to disorder.

Defining the Nature of God

Defining God has become a major problem for the modern theologian because traditional Christian thought combines scriptural ideas with Greek philosophy; Christian orthodoxy mingles biblical personalism and philosophical absolutism.

The notion of God as the Absolute, developed from Plato and Aristotle, is quite different from the God revealed in the Bible. The God of detached philosophical thought is. Not at all the personal God of revelation.

The philosopher's God is an absolute, eternal, changeless, and transcendent being-in-itself. By contrast, the biblical God is the personal Lord, intimately related to men, and responsive to their needs. He speaks to men and listens to their cries for help.

One of the cardinal attributes of the philosopher's God is aseity: God's self-completeness, His absolute independence from the world, and His utter unrelatedness to everything else in creation. Brunner once defined aseity by saying that the world minus God equals zero, but God minus the world equals God.

This kind of God, the God of Neo, is far from the tender, caring, concerned New Testament God of love. Traditional philosophical theology exaggerates the divine intellect at the expense of the divine will.

Due to the influence of Plato and Aristotle, the Church fathers were inclined to be too intellectualism in their descriptions of God, in direct opposition to biblical teaching.

The scriptures reveal the God who acts, rather than the God of contemplation.

Repeatedly in the history of Christian thought, attempts were made to recover biblical voluntarism.

During the Middle Ages, the Dominican Order of St. Thomas stressed the primacy of the intellect, whereas their Franciscan rivals emphasized God's love.

Duns Scorns and William of Ockham, in particular, reasserted the primacy of will over intellect in both man and God.

Luther was trained in this voluntarist tradition and made it the dominant Reformation tradition. Still, another theological issue is the contrast between God as being and God as becoming, which has been a major issue in recent theology. Classical philosophical theism tends to make God static.

He already is the fullness of being, and to think of Him as becoming would make Him less than perfect. But modern thinkers disagree. For example, Macquarrie defines God as the act of being, the act of letting be.

For Macquarrie, being is dynamic.

Process theology goes even further, defining God as becoming rather than being. Because God is deeply involved in the world, He is constantly changing. God is a being who is becoming. From a different philosophical perspective, Wolfhart Pannenberg defines God in terms of the future. God is not yet. Rather, He is a coming reality, to be fully manifested only at the end of history.

Philosophical theism and biblical faith also differ over the personal or impersonal nature of God. In general, philosophers oppose the anthropomorphic description of God found in scripture. Hence, they tend to favor a trans-personal God, one who was not made in man's image.

So God is defined as the Absolute, the unmoved Mover, the First Cause, pure Being, or the Ground of Being. However, in the Bible, God is described in very personal ways. God sees and can be seen; He walks with men; He hears their prayers.

He is interested in what men do and takes an active role in history. God even has a name personifying His authority and power. Moses is told God's name: “I AM; that is who I am” (Ex. 3:13).

Scholars disagree over the exact meaning of this text; however, the important fact is that God is like a man; He is an I. God is always the subject, 'the I am.” Later, the personal God of Moses was reinterpreted as the God of the Fathers.

God is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He is defined in terms of His involvement in Jewish history. YHWH is the God who acts, so His essential nature is identical to His historical actions.

In the New Testament, God is also a personal God. For Jesus, God is “Abba”- a very intimate word meaning “Papa” or “Daddy.” Jesus was the originator of this very personal description of God.

Thus, according to the Bible, God has never been a speculative problem, but rather a living reality. The Hebrews did not try to prove the existence of God, as the Graeco-Roman philosophers did; they took the divine reality for granted. For the Jews, God was the living God, the Lord of history. He was their sovereign, their creator, and their redeemer.

For New Testament Christians, God was also deeply personal. What is God like? He is the Christ-like God. God revealed himself in Jesus as self-giving, self-sacrificing love. God is agape; Love is the essence of His being. To describe God, we must use human words, but this language is always inadequate.

Religious language is almost always symbolic or analogical. An analogy is a comparison made between two objects whose similarity exists within a large realm of unlikeness. For example, when we compare a proud man to a big frog in a small puddle, the differences between the man and the frog are far greater than the resemblances.

Similarly, when we use human language to refer to God, we recognize some likeness between man and God, but the differences are far greater.

Traditionally, Christians have adopted one or more of three methods to describe God's nature: 1) The way of negation has been favored by Christian mystics. God is described by what He is not. God is the Absolute or the Unconditioned. God is not, like ourselves-subject to numerous limitations. God is infinite, not finite as we are.

Thus, we describe God as invisible, intangible, incorporeal, immortal, impassible, etc. All of these are negative attributes ascribed to God, implying that God is not like man.

The way of negation is often used by philosophers to purge anthropomorphism from our notions of God. According to them, it is superstition to believe that God has eyes, hands, a body, or feelings like anger, vengeance, and remorse.

2) Besides the way of negation, theologians employ the way of eminence to describe God. The way of negation raises divine mystery to an infinite level and makes God the Wholly Other, while the way of eminence gives a positive content to our understanding of God.

If we say God is absolute, this means we raise God's sovereign power to an infinite degree. If we say God is eternal, we have expanded His period endlessly. The same process is used when human values are ascribed to God.

If we say He is merciful, kind, just, long-suffering, righteous, and forgiving, we are applying human adjectives to God. But we stretch them: we are loving, God is all-loving; we are merciful, God is all-merciful; we are good, God is all-good.

Neither the way of negation nor the way of eminence is satisfactory by itself. However, when used together, the two methods tend to correct each other.

The weakness of the negative way is its denial of any connection between God and His creation. The weakness of the way of eminence is that it makes God too much like ourselves.

3) Roman Catholic theology relies heavily on the analogy of being (analogic is). By carefully studying the nature of the world, we discover a great deal about the nature of God. The five traditional proofs for the existence of God worked out by Aquinas are based on the analogical is.

Aquinas' five proofs are as follows:

1. Because in our world we see that every motion has a cause, we deduce that God must be the unmoved mover.

2. A similar regression of efficient causes requires God as the first efficient cause.

3. Possible beings require for their existence necessary beings, and the regression of necessary beings must end in a being whose necessity is self-caused-i.e., God.

4. Because our world contains gradations of goodness, truth, etc., there must be a summum bonum which is the cause of all goodness, truth, etc.; this we call God.

5. Because everything is governed by natural laws, which demonstrate design, an intelligent being must exist who directs all natural laws, and this being is God.22 Barth rejected the whole notion of the analogy of being because it overlooks how sin has corrupted both man's reason and the world, and also because it weakens the need for revelation.

And finally, because it assumes that man can discover God on his own. 4) Neo-orthodoxy replaces the analogy of being with an analogy of faith: analogic fidei. The analogy of faith begins with revelation rather than reason.

The analogical implies that man can reason from the facts of nature to faith in God. But the Barthians claim that all our religious knowledge depends upon God's grace. For man to know God, God has to disclose Himself. Thus, we have to rely on God's revelation contained in scripture.

The analogy of faith recognizes that the initiative is taken by God. It starts with revelation and interprets man and nature in light of God's Word. To cite one instance, Barth says that we know what human fatherhood means from the revelation of divine fatherhood, rather than vice versa.

Despite Barth's protest against the analogic entis, many theologians in our time still recognize the value of natural theology. Roman Catholics today call it “fundamental theology.” By this term, they refer to a foundation laid by reason, upon which we can build the superstructure of revealed theology.

Protestant thinkers also believe it is possible to find signs of God in our secular world, apart from the Bible.24 This affirms the importance of natural theology.

The Divine Attributes

How can one describe the characteristics of God's nature?

Theologians call this topic the divine attributes. These have been classified into two groups: the attributes of God's being and the attributes of His activity; what God is and how God acts.

The metaphysical nature of God reveals His basic character. It distinguishes God from all created things.

What makes God God-like?

1) God is God because He possesses all attributes in an infinite measure. As the Sermon on the Mount says, “There must be no limit to your goodness, as your heavenly Father's goodness knows no bounds” (Mt. 5:48).

2) God is an infinite Spirit. 3) God is the absolute Being-Being itself or the Ground of Being. According to Ex. 3:14, God is therefore purely and simply Being: He who is.

God is also personal. Genesis states that man is made in the image and likeness of God. That means that God resembles us because He possesses consciousness, intelligence, will, and heart.

As Brunner said, “God is a Person: He is not an 'It.”'25 Aulen points out that, by insisting on the personal character of God, Christians avoid the mistake that God is either nothing but an impersonal force in nature, or just an abstract idea.

God is Spirit; He is spiritual and not material. He has no physical body.

To quote the Fourth Gospel, “God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth” (4:24).

Because God is pure spirit, He is incorporeal, unconditioned, omnipresent, and unlimited. God is also one. There are not many gods and goddesses, but only one.

The Old Testament says, “Hear, 0 Israel, the Lord is our God, one Lord, and you must love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength” (Dt. 6:4).

Barth tells us that God is one in two distinct ways. 1) God is unique; there is nothing like Him. God is the only one of His kind. 2)

God possesses oneness, whole and undivided, to separate Him from the creation. God is Himself and is not part of the world. He transcends every creature and the whole universe.

But God is also immanent. Psalm 139 reads, “Where can I escape from thy spirit? Where can I flee from thy presence? If I climb to heaven, thou art there; if I make my bed in Sheol, again I find thee” (7-8).

Thus, Clement of Rome in his letter to the Corinthians wrote, “Where, then, shall a man go off or where to escape from Him who embraces all things?” (28:4).

Similarly, Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria declared, “The Divine is not confined to one place, but neither is it absent from any place; for it fills all things, passes through all things, and is outside all things and in all things.”

In addition to God's general presence in the whole universe, there are also special manifestations of His presence and power. He shows His special nearness in His various acts of revelation and reconciliation: in the Hebrew exodus from Egypt, the preaching of the great prophets, and the life and teaching of Jesus, for instance.

Now let us consider God's relationship to man, or His attributes as the God who acts. God is revealed to man as the Creator. Genesis says that in the beginning, God made the heavens and the earth. God saw that His creation was good (1:3, 10, 12, 18, 21, 26), and at the end excellent (1:31).

Everything in creation is a finite replica of the divine perfections. The world is the work of Divine Wisdom because God was motivated by His goodness to create all things. Our world was therefore created to manifest God's glory.

Since God is the creator of all things, He is entitled to expect loyalty and obedience from the entire creation. Thus, theology emphasizes God's sovereignty as one of His major attributes. He is the potter, and we are the clay. He shapes us to His design.

God has made us responsible creatures, whose chief aim in life is to be instruments of His sovereign will. God is our ultimate Master, and we were designed to be His faithful servants.

Since God rules creation and is the lord of history, Christians have deduced two further attributes: God's omnipotence and His omniscience; God must be almighty and all-knowing.

Psalm 135 reads, “Whatever the Lord pleases, that He does, in heaven and on earth, in the sea, in the depths of the ocean” (6).

This implies that God is in absolute control of His creation; He is omnipotent. Omniscience refers to God's complete knowledge. Because He is absolute, He must know everything.

God knows all things in the past, the present, and the future. As almighty and all-knowing, God can exercise total dominion over His creation (Augustine, Calvin, and Barth have held this view).

However, God's omnipotence and omniscience are not absolute, as many theologians have indicated. How could evil ever occur if the rule of a good God is always supreme? How could the Fall have taken place, or mankind become subject to sin if God's will always is carried out?

Process theologians, therefore, qualify the doctrines of omnipotence and omniscience.

First, God is limited by His nature. He cannot will against His nature.

Second, God's power is also restricted by man's free will. So long as men have freedom of choice, God's purpose can be temporarily frustrated.

Third, God must rely upon persuasion in dealing with humans, unless He wants to turn them into robots.

Fourth, if man is truly free and self-realizing, then God's knowledge of the future must be limited to some extent. He knows all the past and present, but concerning the future, he can see only the array of possibilities.

Next, we must mention the personal attributes of God: His grace and holiness, His mercy and righteousness, His pa- patience and wisdom. Barth calls these six attributes the perfections of divine loving.

In each aspect, God resembles man, although these qualities in His nature exist to an eminent degree far superior to their manifestation in ourselves. God is gracious, the giver of every good and perfect gift.

Out of His grace, God seeks fellowship with every person and ties Himself to them with bonds of affection. This is His grace. God freely communicates with us so that we may enjoy union with Him.

Jesus taught the all-encompassing graciousness of the Father in his parable of the Prodigal Son. No matter how much the young man had wasted his life in riotous living, the father was waiting to welcome him home with open arms. His goodwill toward man is unconditional because of His unlimited tenderness.

Hence, Protestants often insist that man is justified by grace alone. God is also infinite holiness.

When Isaiah had a vision of the Lord, high and lifted, he heard the seraphim singing, "Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts" (Is. 6:3).

Omnipresent by the divine holiness, the prophet cried out, “Woe is me! … I am a man of unclean lips and I dwell among a people of unclean lips” (6:5).

Holiness refers to God's awesome supernatural status, His numinousness, in Otto's terminology. God is perfect, and we are imperfect. He maintains the absolute holiness of His will against every other will. Yet, as the scriptures show, the God of absolute holiness is a God of infinite mercy.

According to the Psalms, "The Lord is compassionate and gracious, long-suffering and forever constant" (103:8). "His tender care rests upon all his creatures" (145:9).

Similarly, Jesus taught in the Lord's Prayer that God will always forgive our wrongs when we forgive those who have wronged us (Matt. 6:12). He is ready to share sympathetically in our distress and feels compassion for our suffering. Alongside God's mercy is His absolute righteousness.

The Psalms testify to God's justice: “God is a just judge” (7:11 ); “The Lord is king forever and ever. … Thou hast heard the latent of the humble, Lord, and art attentive to their heart's desire, bringing justice to the orphan and the downtrodden” (10:16-18).

Because God is just, He makes demands on us. He punishes and rewards men for their actions. To enjoy His blessings, one has to be law-abiding and upright. God is infinitely patient. Throughout history, He has given mankind time to mature religiously and morally.

Patiently, He has waited for us to grow in conformity with His will. He watches as we profit from our mistakes and gradually overcome our weaknesses of character. God waits patiently, giving every man freedom and the opportunity to deepen his insights and curb his sinful nature.

Despite all our waywardness and wickedness, God helps us toward the realization of His original plan for our final redemption. In the end, His will shall triumph over every obstacle. God is infinite in His wisdom.

We can be confident in our relations with Him because He is all-wise. He has a design for creation, which has been completely thought out and will be carried to completion. Thus, He can redeem His entire creation and save all men. Swedenborg combined all God's attributes into divine love and wisdom.

Love, together with wisdom, represents the very essence of God. Love and wisdom exist in God as separate faculties, which interact reciprocally, and unite to create the good, which is a manifestation of divine love, and truth, which is a manifestation of divine wisdom.

The same two reciprocal faculties are given to man. The human will exists to experience God's love, and the human understanding exists to benefit from God's wisdom. Through our affections, we can be infused with God's heart, and because of our deep longing for truth, we can breathe in God's wisdom.

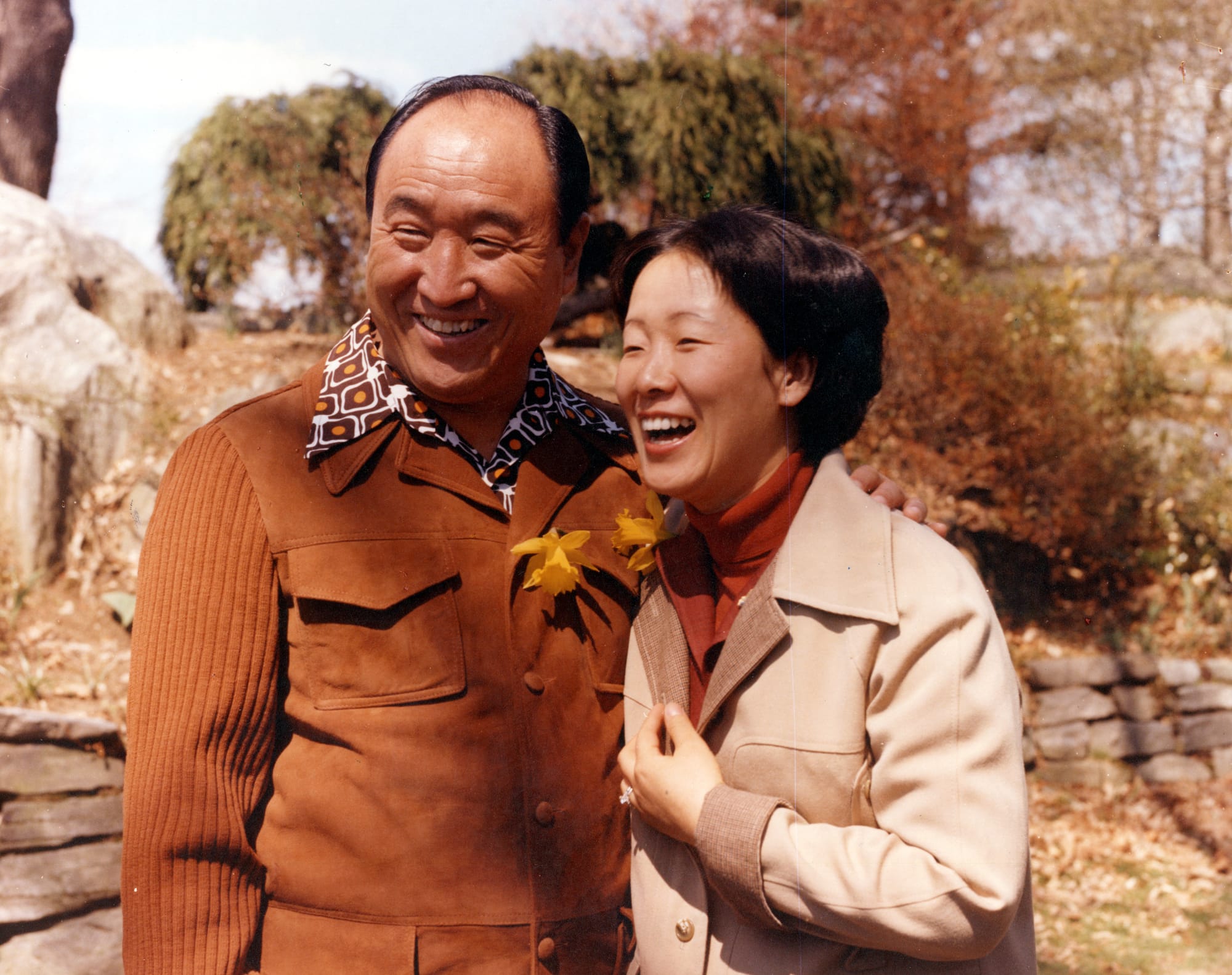

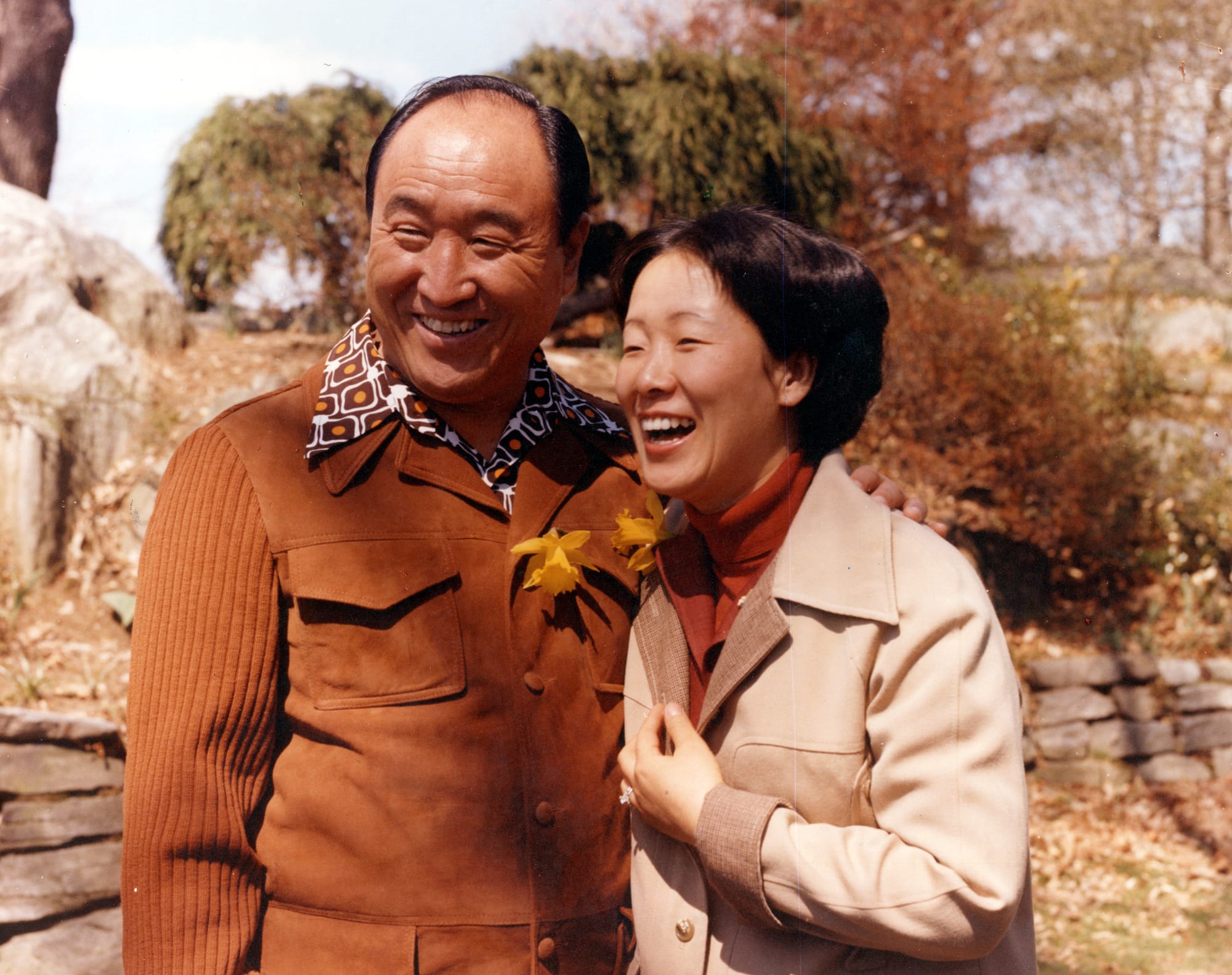

Thus, for both God and man, love exists as the inner substance of life, and wisdom is its outward form. In explaining God's attributes, the Divine Principle has a concept similar to Swedenborg's, but expressed much more concretely.

It is based on Gen. 1:27: “God created man in his image … male and female he created them.”

God's essential nature possesses the characteristics of true fatherhood and true motherhood, in harmonious interaction.

From this interaction, all life-giving energy proceeds. The basic character of God is parental love and creativity. Divine Principle highlights God's heart above ideas like Logos, the Wholly Other, the Ground of Being, the Absolute, or the Unconditioned.

The concept of parental heart encompasses all the attributes that are ascribed to God, such as righteousness and holiness, mercy and forgiveness, sensitivity and suffering, patience and sacrificial love, wisdom, and goodness.

God the Creator

The Apostles' Creed begins, “I believe in God the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth.” So the traditional doctrine of God starts with His work as the Creator. Creation means that everything that exists has its origin and goal in God.

Creation has two aspects. It refers to the creative activity of God, and it refers to the totality of existence, everything in heaven and earth. In Christian theology, creation, providential history, and eschatology belong together.

Creation is about the beginnings; eschatology is about the final destiny of all creatures; and these two are connected by God's providential involvement in all history. According to an existentialist viewpoint, the biblical creation stories are not primitive scientific explanations of the world's origins.

Rather, they illustrate man's continued dependence upon God. Israel derived its knowledge of God not from nature but from history.

God was first known to the Hebrews from His saving acts in their experience as a people. One of the oldest biblical confessions of faith is found in Deur. 26:5-10.

In that creed, the Hebrews explain that they believe in God because He liberated them from slavery in Egypt. There is no mention at all of the creation of the world. The creation stories appeared late in the monarchial age of Israel. The Hebrews became men of faith because of God's saving acts in their national history.

Through their experiences of God's presence in history, they gradually deduced that He was in nature, the universal Creator. Christians have held two opinions about how creation took place: creation out of nothing and creation out of God.

These theories are called creation ex nihilo and emanationism.

Creation ex nihilo teaches that rather than creating everything out of pre-existent eternal matter, God simply spoke, and the world appeared, rather like a magician pulling a rabbit out of an empty hat.

The words “creation out of nothing” are not found in Genesis 1, but first occur in 2 Maccabees 7:28.28.

What are the merits of this doctrine?

1) It asserts God's transcendent power.

2) It separates God from creation and thus denies pantheism.

3) It affirms that the world is good because God created it.

4) Since God made the world, He is entitled to use it and rule over it. Creation is dependent upon its Maker and has no self-sufficiency.

But creation ex nihilo suffers from serious weaknesses.

1) It does not fit the scientific explanation that our world was made from energy. 2) It ignores the closeness of God to man and the world, God's immanence.

3) It desacralizes creation and can lead to ruthless exploitation of our material resources, producing the ecological problems of our day.

The alternative view is that God creates the world out of His nature. He is like a mother producing a child. Or the world is like the water flowing out of a divine spring.

God creates out of His inexhaustible nature, and the world is an emanation of His power, vitality, and love. Hence, God is the Father/Mother to the creation. The merit of the emanation doctrine is that God, man, and the world are intimately related.

God's being is revealed in nature, and particularly in man. As Paul said, all things live and move and have their being in God. Nature is not alien to God, but is a manifestation of His essential creativity.

Hence, the emanations view has been favored by mystics like Dionysius the Areopagite, Jacob Boehme, Swedenborg, idealistic philosophers, 30, and religious scientists of our time. 31 Creation, they say, is the natural expression of God's overflowing love, and man is truly His offspring.

Emanationism also supports the idea of continuing creation. God's work was not finished in six days or 6000 years or at any time in the past. God continues to create because that is His essential nature.

God reveals Himself and manifests His boundless creativity in every flower, every sprout of green grass, and all the developing cultures of mankind. This idea of continuing creation is important for theologians such as Teilhard de Chardin, who attempts to reconcile religion and modern science. Neo-evangelicals and Fundamentalists expound Christ's role in creation.

This does not make sense if it means that Jesus the man existed from all eternity and helped God in creating the world. However, it is possible to hold a Christocentric interpretation of creation (John l; Col. 1 15-17, Heb. 1:2-3).

The New Testament focuses on the need for a new creation and a new covenant. God needs to restore the world to its original beauty and goodness. Christ, therefore, came as the new Adam, as Paul teaches.

The Logos (God's wisdom) was present with God at the beginning of creation, and Jesus Christ was chosen by God to embody and fulfill man's original purpose.

Creation ex nihilo and emanationism explain how creation took place. But why does it exist? What is the purpose of creation? In our discussion of the divine attributes, we pointed out that God is a God of the heart whose essential nature is love.

Love is always a two-way relationship. And the goal of the heart is to feel joy. Christians say that God seeks fellowship with man. He wants to express His love, yet love remains incomplete until it is reciprocated. Even God requires an object for the give and take of His affectionate nature. The man was thus made to be God's partner, the object of His love.

Productive activity is generated through this divine/human relationship and interaction. As a union of body and soul, man requires both a physical and spiritual environment. Hence, the world was created to satisfy man's needs. He must interact with the physical universe as well as the spiritual world to have a healthy, happy life.

God is glorified by man's grateful obedience and response to divine love, and by the whole creation. God needs man as the mediator between Himself and the physical universe.

Through man's give and take with everything in creation, the material world becomes a substantial object to God and gives Him pleasure.

Thus, God manifests Himself through the whole universe, so the creation is God's body, a revelation of His nature, and an instrument of His purpose. As the Psalmist says, “The heavens tell out the glory of God, the vault of heaven reveals his handiwork” (19:1).

References

4 Bertrand Russell and F. C. Copleston, “A Debate on the Existence of God,” in The Existence of God, ed. John Hick (New York: The Macmil- lan Company, 1968), pp. 168-178. 5 A. E. Taylor, “Nature and Teleology,” in The Cosmological Arguments, ed. Donald R. Burrill (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1967), p. 211. A more sophisticated case can be made for goal-directed evolution based on the increase in complexity of living organisms, and particularly on the rise of consciousness; Teilhard de Chardin has been the leading exponent of this view (see The Phenomenon of Man (New York: Harper & Row, 1957)). 6 Stanley L. Jaki, The Road of Science and the Ways of God (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978). 7 The Critique of Practical Reason, Book II, Ch. II, Sec. V. 8 Hastings Rashdall, The Theory of Good and Evil, Vol. II (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907), pp. 206-213. 9 Richard Swinburne, The Existence of God (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979). 10 Ibid., p. 5. 11 Ibid., p. 7. 12 Ibid., p. 66. 13 Ibid., p. 67. 14 Ibid., pp. 93-106. 15 Ibid., pp. 131-132. 16 This is the conclusion of Wallace I. Matson's The Existence of God (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1965 ), pp. 242-244. 17 Biblical voluntarism: the Hebrews believed that the will was more important than the intellect; we will first, and reason later. For a survey of contemporary natural theology, see E. L. Mascall, The Openness of Being (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1971). 2 For a good selection of sources and contemporary treatments, see Alvin Plantinga, ed. The Ontological Argument (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1965). 3 In The Laws, Plato proves the existence of God from the fact that the change and motion we see in nature must have a first cause. Something with self-motion has to exist to explain the origin of the change we see in the world. God, then, is the “the eldest and mightiest principle of change. “ Starting with our recognition of natural movement -for example, the wind shaking the leaves of a tree-we must find.